Summary

Working in mice, scientists supported in part by the NIH’s National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases (NIAMS) have found that two molecules involved in the inflammatory response also directly activate itch-sensing neurons and trigger the itch sensation. Blocking the molecules’ effects with a medicine used to treat rheumatoid arthritis provided relief in a group of patients experiencing chronic itch that had not responded to other treatments. The findings, which appeared in Cell, suggest that targeting inflammatory pathways could lead to new ways to treat neuronal conditions like chronic itch.

Background

Chronic itch is the primary feature of a number of skin conditions, such as eczema and psoriasis. Itching also occurs in a variety of other diseases and as a side effect of certain drugs. In addition, some people experience chronic itch with no known cause, a condition dubbed chronic idiopathic pruritus. Chronic itch impacts millions of Americans, yet there are currently no medicines that specifically treat it.

The causes of chronic itch are poorly understood, but a clue has come from the strong link between itch and skin inflammatory conditions like atopic dermatitis, the most common form of eczema. Research has shown that the inflammatory molecules IL-4 and IL-13 are associated with itch in atopic dermatitis, but the sensation-triggering molecular mechanisms have been unclear. A better understanding of these mechanisms could lead to new insights on how to treat chronic itch.

IL-4 and IL-13 Activate Sensory Neurons and Trigger Itch

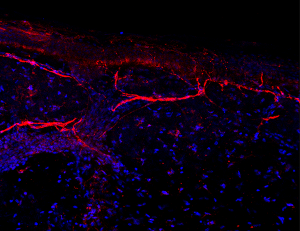

In the current study, investigators led by Brian S. Kim, M.D., of the Washington University School of Medicine, set out to provide some clarity. They first showed that IL-4 and IL-13 activate mouse sensory neurons cultured in the laboratory. IL-4 treatment triggered activation of cultured human sensory neurons as well.

The team next wondered if neuronal activation occurs in the same way as in immune cells, where IL-4 or IL-13 binding to the IL-4 receptor on the cell surface stimulates the JAK1 enzyme inside the cell. Subsequent steps in the pathway would then be expected to lead to firing of the neuron and transmitting the signal to the brain.

To investigate this classical immune pathway’s role in neurons and itch, the researchers engineered groups of mice that lack either the IL-4 receptor or JAK1 in sensory neurons. If these molecules work as in immune cells, absence of either one would be expected to impede neuronal activation and dampen the itch sensation.

The results bore out this premise. Both types of engineered mice scratched less than control mice when treated with a chemical that produces atopic dermatitis-like skin inflammation.

Encouraged by these findings, the investigators next set out to explore the possibility that a drug already on the market called tofacitinib, which works by blocking JAK1’s enzyme activity, could be effective in treating itch. Tofacitinib is normally used to target the overly active immune system of rheumatoid arthritis patients, reducing the pain and joint inflammation that characterize the condition.

When the researchers tested tofacitinib in a group of five patients with chronic idiopathic pruritus, all of them reported marked improvement, with relief occurring within days. On average, they experienced 80 percent reduction in symptoms following one month of treatment. While these results are promising, the authors caution that they must be validated in a larger study.

“This work is a compelling example of how studying disease mechanisms can reveal new uses for existing drugs,” said Dr. Kim. “The overlap between immune and neuronal signaling pathways that we uncovered has provided us with a valuable shortcut to a new therapeutic approach for chronic itch.”

This work was supported by the NIH’s NIAMS (R21-AR068012, K08-AR065577, R01-AR070116), National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (UL1-TR000448), the National Cancer Institute (P30-CA091842), the National Center for Research Resources (S10-RR027552), the National Institute of Neurological Diseases and Stroke (R01-NS042595), the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (P30-DK052574, R01-DK103901), the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (R01-GM101218) and the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (T32-HL007317). Additional funding was provided by the American Skin Association, the Doris Duke Charitable Foundation, the Howard Hughes Medical Institute and LEO Pharma.

Learn More About Research on Itch

- Socially Contagious Itching Hardwired Into Brain

- Ion Channel Found to Play Role in Itch Sensation

- Investigating the Causes of Chronic Itch: New Advances Could Bring Relief

- Serotonin Drives Vicious Cycle of Itching and Scratching

- Who Knew? A Neural Circuit Just for Itching

#

Sensory Neurons Co-opt Classical Immune Signaling Pathways to Mediate Chronic Itch. Oetjen LK, Mack MR, Feng J, Whelan TM, Niu H, Guo CJ, Chen S, Trier AM, Xu AZ, Tripathi SV, Luo J, Gao X, Yang L, Hamilton SL, Wang PL, Brestoff JR, Council ML, Brasington R, Schaffer A, Brombacher F, Hsieh CS, Gereau RW 4th, Miller MJ, Chen ZF, Hu H, Davidson S, Liu Q, Kim BS. Cell. 2017 Sep 21;171(1):217-228.e13. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.08.006. Epub 2017 Sep 7. PMID: 28890086

The mission of the NIAMS, a part of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services' National Institutes of Health, is to support research into the causes, treatment and prevention of arthritis and musculoskeletal and skin diseases; the training of basic and clinical scientists to carry out this research; and the dissemination of information on research progress in these diseases. For more information about the NIAMS, call the information clearinghouse at (301) 495-4484 or (877) 22-NIAMS (free call) or visit the NIAMS website at https://www.niams.nih.gov.