A new drug appears to alter the expression of certain genes associated with systemic sclerosis by blocking a key protein, and also leads to clinical improvements in the skin, according to a study funded in part by the NIH’s National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases (NIAMS). The study was published in the Journal of Clinical Investigation.

Systemic sclerosis, a severe form of scleroderma, is a chronic connective tissue disease that affects multiple organs and tissues in the body. It can lead to fibrosis, or hardening, of the skin and other organs such as the lungs, kidneys and heart. Currently, no effective treatments exist. Because the disease affects everyone differently, finding therapies has been challenging.

Previous research in animals has implicated a protein called transforming growth factor (TGF-beta) and two of the genes it regulates—Thbs1 and Comp—in the development of fibrosis, but no clinical data has been found to directly support its role in humans with scleroderma. Moreover, the most commonly used clinical tool to measure the disease progression, the modified Rodnan skin score (MRSS), is not especially sensitive to change and requires long time frames and repeated follow-ups to identify progression of skin disease. "If certain biomarkers could be used to detect therapeutic effects earlier in the treatment process, and we could correlate these biomarkers with clinical outcomes, we may be able to save valuable time and speed up clinical treatment decision-making for these patients," said lead investigator and NIAMS grantee Robert Lafyatis, M.D., of the University of Pittsburgh. Lafyatis conducted the study while at the Boston University School of Medicine.

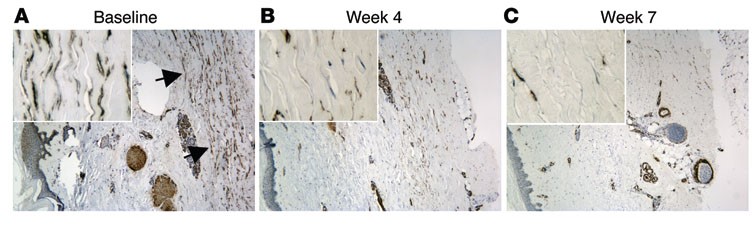

Lafyatis and colleagues designed a clinical study to examine the effect of a new, not-yet-approved drug that blocks all forms of TGF-beta. The drug, called fresolimumab, was given intravenously to 15 patients in the early stages of scleroderma. Eight of the patients received one large dose, and seven received two small doses four weeks apart. The skin of each patient was biopsied at the beginning of the trial, and several times after the drug was administered.

In both groups of patients, THBS1 and COMP expression significantly declined three to seven weeks after patients received the drug. In addition, skin condition improved clinically, as measured by the MRSS, further implicating these genes in skin fibrosis. This rate of fibrosis reversal has not been seen in any previous clinical trials, according to the researchers. By week 24, however, patients began to experience disease recurrence as the effects of the drug diminished, indicating that future studies involving treatment with fresolimumab will need to be longer in duration. In addition, a larger, placebo-controlled clinical trial is needed to confirm the findings.

Skin fibrosis itself does not cause death in patients with scleroderma, but fibrotic disease affecting internal organs can be fatal. "Skin hardening shares features with fibrotic disease in other organs and sites within the body, suggesting that drugs that treat skin may also show promise for other involved organs. And because skin can be biopsied more easily than other organs, it provides a window into understanding how the disease may be progressing, and how other target organs may respond to the treatment," said Lafyatis. Moreover, the study results demonstrate the value of a biomarker-based approach to measuring treatment response and confirming clinical data.

This work was supported by NIAMS (grant numbers P30-AR061271, P50-AR060780, and R01-AR051089) and by the NIH’s National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences. Additional support was provided by the Kellen Foundation at the Hospital for Special Surgery, the Scleroderma Research Foundation, and the Dr. Ralph and Marian Falk Medical Research Trust.

# # #

Fresolimumab treatment decreases biomarkers and improves clinical symptoms in systemic sclerosis patients. Rice LM, Padilla CM, McLaughlin SR, Mathes A, Ziemek J, Goummih S, Nakerakanti S, York M, Farina G, Whitfield ML, Spiera RF, Christmann RB, Gordon JK, Weinberg J, Simms RW, Lafyatis R. J Clin Invest. 2015 Jul 1;125(7):2795-807. Doi:10.1172/JCI77958. Pubmed PMID: 26098215.

The mission of the NIAMS, a part of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services' National Institutes of Health, is to support research into the causes, treatment and prevention of arthritis and musculoskeletal and skin diseases; the training of basic and clinical scientists to carry out this research; and the dissemination of information on research progress in these diseases. For more information about the NIAMS, call the information clearinghouse at (301) 495-4484 or (877) 22-NIAMS (free call) or visit the NIAMS website at https://www.niams.nih.gov.