Muscle exertion is necessary to ensure the development of a functional, structurally sound connection between tendon and bone in young mice, according to recent research funded by the NIH’s National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases. The research was published in the journal Bone.

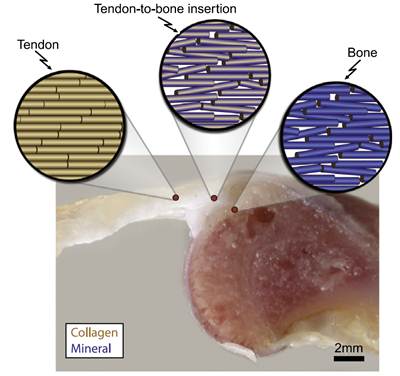

The point at which tendon and bone connect is a highly complex structure that is sensitive to disruption during development. It is particularly vulnerable to injury, and can be difficult to heal. Surgery to reattach dislodged tendon-bone connections often fails, as well. Having a better understanding of how the junction initially forms and develops, and what conditions are necessary to ensure a healthy interface, may allow for more successful repairs after damage has occurred.

“Previous studies have found that, for musculoskeletal tissues to develop normally, they must be exposed to certain external stress or forces—what is known as ‘muscle loading,’” said senior author Stavros Thomopoulos, Ph.D., of Washington University in St. Louis. “But the consequences of reduced or absent muscle loading on the structure and functionality of the tendon-bone interface while it is developing have not been adequately explored.”

The researchers focused on a condition found in about 1 percent of newborns called neonatal brachial plexus palsy (NBPP), an injury that can occur during birth and cause shoulder paralysis. Other problems can result from NBPP, including reduced range of motion or bony defects which can be attributed to the lack of muscle forces on the developing tissue. Children with severe cases may not be able to use their shoulder at all. To determine how NBPP and the muscle “unloading” associated with it can affect the development of the tendon-bone junction, the researchers recreated the condition in young mice. They injected a toxin into the shoulders of one group of mice, which temporarily paralyzed the affected area, and compared these injected mice with normal mice over time to determine how tendon growth and interface development were affected by muscle unloading.

Consistent with previous studies, the tendon continued to grow at roughly the same rate in both groups of mice. Other research has indicated that mature tendons may shrink if they are not subjected to consistent muscle loading, but young tendons will continue to grow even in the absence of muscle use. This suggests that developing tendons respond differently to unloading compared to mature tendons, the researchers note. However, after four weeks of paralysis, the shoulders of the mice injected with the toxin showed diminished range of motion compared to normal mice. The tendon-to-bone interface structure appeared to be mechanically weaker than those of nonparalyzed mice, especially after eight weeks of paralysis. In addition, compositional analyses indicated that the muscle unloading resulted in less organized and misaligned collagen cells within the cartilage of the interface, as well as reduced tendon strength.

“Understanding the vital role of muscle loading, especially during key developmental stages in the weeks after birth, will eventually help us design a more effective strategy for treating these types of injuries,” said Thomopoulos. Further research is needed to determine at what point surgical repair may be most beneficial, and to what extent these deteriorations at the interface are reversible once functioning and muscle loading are restored.

The study was funded by the National Institutes of Health under award numbers R01AR055580, P30AR057235, and T32AR060719.

Muscle loading is necessary for the formation of a functional tendon enthesis. Schwartz AG, Lipner JH, Pasteris JD, Genin GM, Thomopolous S. Bone. 2013 Jul;55(1):44-51. Epub 2013 Mar 29. PMID: 23542869.

The mission of the NIAMS, a part of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services' National Institutes of Health, is to support research into the causes, treatment and prevention of arthritis and musculoskeletal and skin diseases; the training of basic and clinical scientists to carry out this research; and the dissemination of information on research progress in these diseases. For more information about the NIAMS, call the information clearinghouse at (301) 495-4484 or (877) 22-NIAMS (free call) or visit the NIAMS website at https://www.niams.nih.gov.